The British Museum houses many of the most famous works of art especially from ancient times and from around the globe. It is the oldest public museum in the world established in 1753 to house the collections and library of Sir Hans Sloane and by the 19th century had outgrown its facilities, so a grand and very large museum in the neoclassical style was built. In 2000 the rotunda with glass ceiling was added to bring a number of separate buildings together and the round library still houses some of the original Sloane library. That has only recently been opened to the public to see though the books are not available except to scholars.

The Rosetta Stone is probably the most famous work in the museum’s collection and important for so many reasons. If you are in my ancient art history class we have talked about early writing and deciphering it has always been a challenge. When this stone was discovered in Egypt it had three registers, the top in hieroglyphs, middle in demotic (a kind of daily ancient Egyptian slang) and Greek at the bottom. Greek had been understood for some time so this allowed scholars to decipher to top two scripts. A major breakthrough. So one question comes up, if this work is from ancient Egypt how did it end up in the British Museum? Actually since most of the work in the museum is NOT from Britain how did they come to have most of it?

I’ll leave that question for a bit and focus on some of the treasures in the museum that do come from Britain. In our class we’ll be learning about the Sutton Hoo Burial. Here’s the story. Located on the eastern coast of Britain a woman decided to have some mounds on her property excavated to see what might be inside. What they discovered was the remnants of a burial ship (the wood was gone) with the metal hardware still in place and filled with a trove of treasure including the helmet you see on the left. I’ve seen this many times in books but in person for the first time. I never realized there is a creature created by the eyebrows and the front of the helmet down to the nose. Another interesting discovery in another location were these chess pieces. A man in Scotland was walking along and saw these heads sticking up out of the ground. He was scared they were demons and ran to tell his wife, she made him go back and dig them up and here they live in the British Museum. They are delightful. They are made from walrus bone and date from the 12th century. The Bishops are called berserkers because they are biting down on their shields, that was a new one to me.

One last piece to talk about before going beyond Britain in their collection. This stone axe dates back 100,000 years. Amazing to see something like that. It was found with the skeleton of an elephant which obviously was not native to Great Britain. It is guessed that people and animals migrated from the mainland of Europe to Britain and may have brought animals or it was coincidental that the axe was there when they found the elephant that we know the Romans brought with them when they conquered.

These are cuneiform tablets from Ashurbanipal’s palace excavated in what we now know of as Iraq that was called Mesopotamia in ancient times. So why does the British Museum have these? To be fair when archaeologists in the past have done their work, they often took with them what they found back to their home countries. That does not happen anymore unless with permission from the host country but for centuries it did and that’s one of the ways the museum established its collection. There’s also spoils of war and actual theft. It’s a complicated issue and more and more there are efforts to repatriate art works back to their countries of origin.

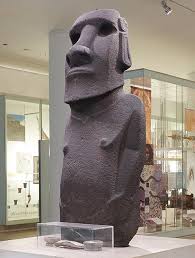

Chinese vases from the Yang dynasty said to be among the finest porcelain vases in the world, stone lovers from near Bethlehem 11,000 years old, and a Moai statue from Easter Island. The vases were “collected” meaning purchased but always wonder how the dealer got them and the Moai is a smaller one and they still have “lots of them” on the island and it’s protected here so it’s okay.

We ended our visit to the British Museum in the Parthenon room where the statues and friezes from the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens once stood. They were plundered by Lord Elgin in the 19th century, a well known fact and now they are not known as the Elgin marbles anymore, this is known as the Parthenon room and has some benefactor’s name associated with it. To be fair it is a complicated issue, Greece has been asking for these works back and even built a museum to house them when they hosted the Olympics. The British Museum never sent them back. It takes an act of parliament to agree to this which so far hasn’t happened. When you walk through the museum and see works that are likely have been destroyed if they had remained in their home countries are returned there it complicates things even more. No simple answer. However, I noticed the museum does not acknowledge anything about this anywhere that I could see. That is not the case with the Tate Britain and its legacy.

The Tate Britain is housed in another neoclassical building along the Thames. It houses the country’s largest collection of British art spanning the 16th to the 21st centuries (most of the modern art can be found at Tate Modern in another location). JMW Turner has his own set of galleries with 300 spectacular paintings and 20,000 sketches. Henry Tate, a sugar merchant provided the initial collection at the end of the 19th century. Upon entering the building one of the first things you see is acknowledgment that the Tate has a legacy that involved slavery. The museum is working to address these legacies through research, interpretation, and dialogue. Some of that appears in the captions for works on display and special exhibits bring diversity into the museum space.

JMW Turner’s “Ploughing Up Turnips” 1809 suggests Turner’s empathy for the peasants. The caption accompanying the painting talks about the start of corporate farming and its affect on peasants.

JMW Turner’s “The Deluge” 1805 shows a black man rescuing a white woman and the informational caption explains that this painting was completed when the cause of abolition of slavery in Britain was gaining ground. That makes this detail significant. Turner later dedicated a print of this work to Lord Carysfort, a pro abolition MP.

In another part of the museum is a new installation by Chris Ofili, a British artist of African descent. This is titled “Requiem” new installation by Chris Ofili, and fills the whole space. It is in honor and memory of those who lost their lives in the Grenfell Tower fire in 2017 when a skyscraper apartment building in central London caught fire and turned into an inferno. It housed immigrants and while the official figure says 70 people were killed its likely many more lost their lives jumping from the building but since they were unregistered the total loss of life will never be known. The artist says the work “offers a journey through an imagined landscape of giant skies with vast horizons along flowing water to reflect on loss, spirituality, and transformation.”

Comments